Browning v. Colvin, -- F.3d --, No. 13-3836 (7th Cir. Sept. 4, 2014)

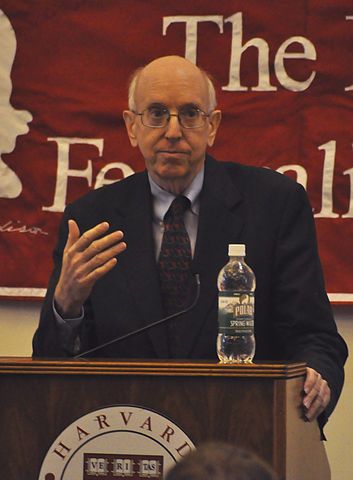

The Seventh Circuit (Judge Posner) published another very helpful pro-claimant case this week.

Browning v. Colvin, -- F.3d --, No. 13-3836 (7th Cir. Sept. 4, 2014) http://tinyurl.com/Posner-vocationalBrowning explains in part:

There is more that is wrong with the administrative law judge’s assessment of the jobs that the plaintiff might be able to fill. Remember that “hand packer” comes first in the vocational expert’s list, and in the administrative law judge’s list as well (for he appears to have relied on the vocational expert’s advice), of jobs the plaintiff can fill. The vocational expert did not describe the job of a “hand packer”; she merely cited to a section of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, a compendium of job descriptions published by the Department of Labor. But the section she cited to, DOT 920.687-030, is not captioned “hand packer,” but “hand bander (tobacco)”—a worker who wraps cigars. Nevertheless the administrative law judge cited the same section in concluding that the plaintiff has the residual functional capacity to be a hand packer. For all we know, the plaintiff could wrap cigars, but needless to say the vocational expert did not indicate how many tobacco hand bander jobs exist in the area, region, or nation.There is no occupational title “hand packer.” The closest is “hand packager.” U.S. Department of Labor, Dictionary of Occupational Titles, § 920.587-018 (4th ed. 1991). We set forth its description in full in the appendix. It is apparent from the description that many of the jobs are beyond the plaintiff’s capacity to do. And there is no indication that the administrative law judge, or for that matter the vocational expert, was even aware of the DOT’s hand-packager description.

A further problem is that the job descriptions used by the Social Security Administration come from a 23-year-old edition of the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, which is no longer published, and mainly moreover from information from 1977—37 years ago. No doubt many of the jobs have changed and some have disappeared. We have no idea how vocational experts and administrative law judges deal with this problem. We also have no idea what the source or accuracy of the number of jobs that vocational experts (including the one in this case, whose estimates the administrative law judge accepted without comment) claim the plaintiff could perform that exist in the plaintiff’s area, the region, or the nation. There is no official source of number of jobs for each job classification in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles, and while there are unofficial estimates of jobs in some categories, the vocational experts do not in general, and the vocational expert in this case did not, indicate what those data sources are or vouch for their accuracy. And many of them estimate the number of jobs of a type the applicant for benefits can perform by the unacceptably crude method of dividing the number of jobs in some large category (which may be the only available data) by the number of job classifications in the category, even though there is no basis for assuming that there are, for example, as many mophead trimmer-and-wrappers, DOT 789.687-106, as there are fish-egg packers, DOT 529.687-086, or poultry-dressing workers, DOT 525.687-082—all being hand-packager jobs.

Most serious, perhaps, as far as we’re able to ascertain there are no credible statistics of the number of jobs doable in each job category by claimants like the plaintiff in this case who have “limitations,” in her case mental retardation, obesity, and the residual effects of her childhood disease of the leg. The vocational expert’s statistics were for all jobs in categories in which some jobs, but clearly not all, might be within the plaintiff’s capacity to perform. For useful discussions of these and other problems encountered in trying to estimate the number of jobs in area, region, and nation that applicants for benefits can perform, see, e.g., Peter Lemoine, “Crisis of Confidence: The Inadequacies of Vocational Evidence Presented at Social Security Disability Hearings,” 2012, www.lemoinelawfirm.com/wp-materials.pdf; Nathaniel Hubley, “The Untouchables: Why a Vocational Expert’s Testimony in Social Security Hearings Cannot Be Touched,” 43 Valparaiso Valparaiso Law Review 242 (2008), and references cited in these articles. Link to Lemoine: http://www.lemoinelawfirm.com/disability-advocates-handbook/

Link to Lemoine: http://www.lemoinelawfirm.com/disability-advocates-handbook/

It was wonderful to see the ideas from my book and those from my friend Attorney Bob Angermeier flowing from Judge Posner's pen.

Other important issues addressed with considerable bite in Browning include the ALJ's playing doctor, unfounded presumptions about mental retardation, boilerplate credibility determinations that invert the credibility process, faulty ALJ logic, physical and mental RFC, obesity, and whether ability to get to work is a factor to be considered when evaluating step five.

The decision is another broadside at SSA, and as such, it should be used with care. For example, the mental retardation listing does not say what Judge Posner says it says. Proceed with care when you use Judge Posner's discussion of sarcasm and Chimpanzees.

In any event, it is another in an unbroken string of published 7th circuit cases in 2014 blasting the SSA.